How we got the Sign of Peace at Mass

HOW WE GOT “THE SIGN OF PEACE” AT MASS

The Sign of Peace or “holy kiss,” as St. Paul calls it (Cf. Rom. 16:16), has almost always been an important part of the Mass.

From the Early Church

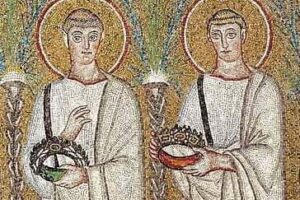

In the early Church, originally, the Kiss of peace was a full, lip-on-lip act and was given to members of the same and opposite sex. The liturgical kiss was seen as an intimate gesture, the kind of thing one would only do within one’s family. Christians, those baptized in Christ, are now the new family of the children of God (Cf Gal. 3:17). Hence, the Kiss was not given to “non-family members” such as non-Christians, those who had left the Church or even catechumens. This was quite easy to see since in the early Church the non-baptized (catechumens) were dismissed (made to leave the Mass) after the homily before the Kiss of peace took place. It was only those who were baptized that could stay at Mass till the end. This is why the Liturgy of the Word of the Mass was called the Mass of the Catechumens.

However, by the late second century, there were some “abuses” of the practice with some people “taking advantage” of the kiss on the lips. To solve the problem, men and women were separated at Mass and were seated on the opposite sides of the nave (this “separation” of sexes at Mass, though might sound strange to us today, continued in the Church for centuries. Interestingly, as late as 1917, the Code of Canon Law at the time, still recommended this practice). The Kiss of peace continued to remain a vital part of the liturgy until the mid-1200s, when it began to fall into disuse and gradually was no longer part of the Mass.

From the 1570s when the Church tried to revive the rite, the actual kissing was then no longer a part of it. Rather, the giver of the peace placed his hands on the recipient’s shoulders and leaned forward towards his left cheek saying “Pax tecum” (Peace be with you) to which the recipient replied “Et cum spiritu tuo” (And with your spirit). The act of falling on someone’s neck betokens a kiss and comes from a biblical background of the father kissing his prodigal son in Luke 15:20 (“But while he was yet afar off, his father saw him, and was moved with compassion, and ran, and fell on his neck, and kissed him”). Till today, this gesture for the Kiss of peace is still used by some clergy.

The Kiss of peace later took the form of the priest kissing a paten-like object called a “pax-brede” and then passed it on the Mass servers and then on to the congregation in order of rank. This too brought some challenges because of disputes within the laity over who outranked whom (“who is who”). Thus, by 1962, this form of the kiss of peace was restricted to the most notable dignitaries present; the laity as a whole, ceased taking part in it.

Placing of the Kiss of Peace (Conciliatory Kiss and Paschal Kiss)

Another important feature of the Kiss of peace in the early Church is that it was not always given before Communion took place. There were actually two moments during Mass when it took place depending on the rite used for Mass celebration. All Eastern rites placed the Kiss somewhere around the Offertory (before the procession with the gifts), while the churches in Rome and North Africa placed it after the Consecration (before the reception of Holy Communion). Till today this difference in the position of the Kiss of Peace at Mass still exists between the Eastern rites and the Roman rite.

Those following the example of the Eastern rites who place it around the Offertory maintain that the Kiss of peace is inspired by our Lord’s admonition to “be reconciled to thy brother” before offering “thy gift at the altar” (Matt. 5, 23-24). For this reason the “Eastern Kiss” is shared by members at Mass just before the gifts of bread and wine are presented at the altar and thus may rightly be called the “conciliatory kiss”.

On the other hand, the “Roman Kiss”, which is offered after the Consecration, which we may label the “paschal kiss,” takes its bearings not from the Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5, 23-24) but from the Paschal mystery stretching from the Last Supper to the Resurrection. In the story of the disciples of Emmaus, the risen Lord meets two men, explains the Scriptures to them, and is recognized by them only in the breaking of the bread. Significantly, the text does not state that they went on to eat but that they raced back to Jerusalem to tell the Apostles, and that when they were describing what had happened, Jesus stood in their midst and said, “Peace be to you” (Luke 24:35-36). The story then ends by stating that Christ, to prove that He was not a ghost, ate some food and gave it to the others to eat. In other words, the Emmaus Resurrection story gives us the traditional Roman order of the Mass; from the Liturgy of the Word (Christ explaining the scriptures to the men) to the “fractio panis” (breaking of the bread by Christ) to the kiss of peace (Jesus saying “Peace be to you”) and then to the communion rite (Jesus taking some food and giving it to others to eat). Thus, in the Roman rite, the Kiss of peace is shared before Communion to emphasize precisely this paschal dimension of the gesture.

The Kiss of Peace today

In 1970, following the Second Vatican Council, the Church once again, opened the Kiss of peace to the whole congregation; everyone at Mass now takes part in it. The priest says to the people: “Offer each other the sign of peace”, and then, as the rubrics indicate: “And all signify to each other peace and charity, in accordance with local custom.” The “local custom” used here has now almost universally taken the form of a handshake which is certainly a sign of peace, but more from a secular understanding. Handshaking indicates that One is unarmed. It signifies a truce or deal, the kind of agreement one makes in politics and business. However, it is not primarily a sign of love or intimacy, as the liturgical kiss of peace signifies. Basically, handshakes during Mass and handshakes outside the liturgy could be interpreted in the same way; a gesture of welcome, a deal, etc., thus falling short of the liturgical significance of the Kiss of peace as a gesture of love and intimacy as practiced by the early Christians.

In the absence of a more wholistic “sign of peace” with the proper liturgical meaning intended, our current “handshake Kiss of peace” will continue to be the option. It is rather important for us to understand that whenever we extend the Sign of peace at Mass, we are not merely “saying hi” or welcoming our family and friends at Mass; that would be reducing the Kiss of peace to a secular understanding of the gesture. Our Sign of peace is rather a sharing in the “Peace of Christ”; the peace that the Resurrected Christ passed on to his disciples. In the end, the Kiss of peace remains the sign of a truly resurrected community of believers gathered in worship.

Compiled By: Fr. Anthony Agnes Adu-Mensah.

(Rome, 07.06.2023)